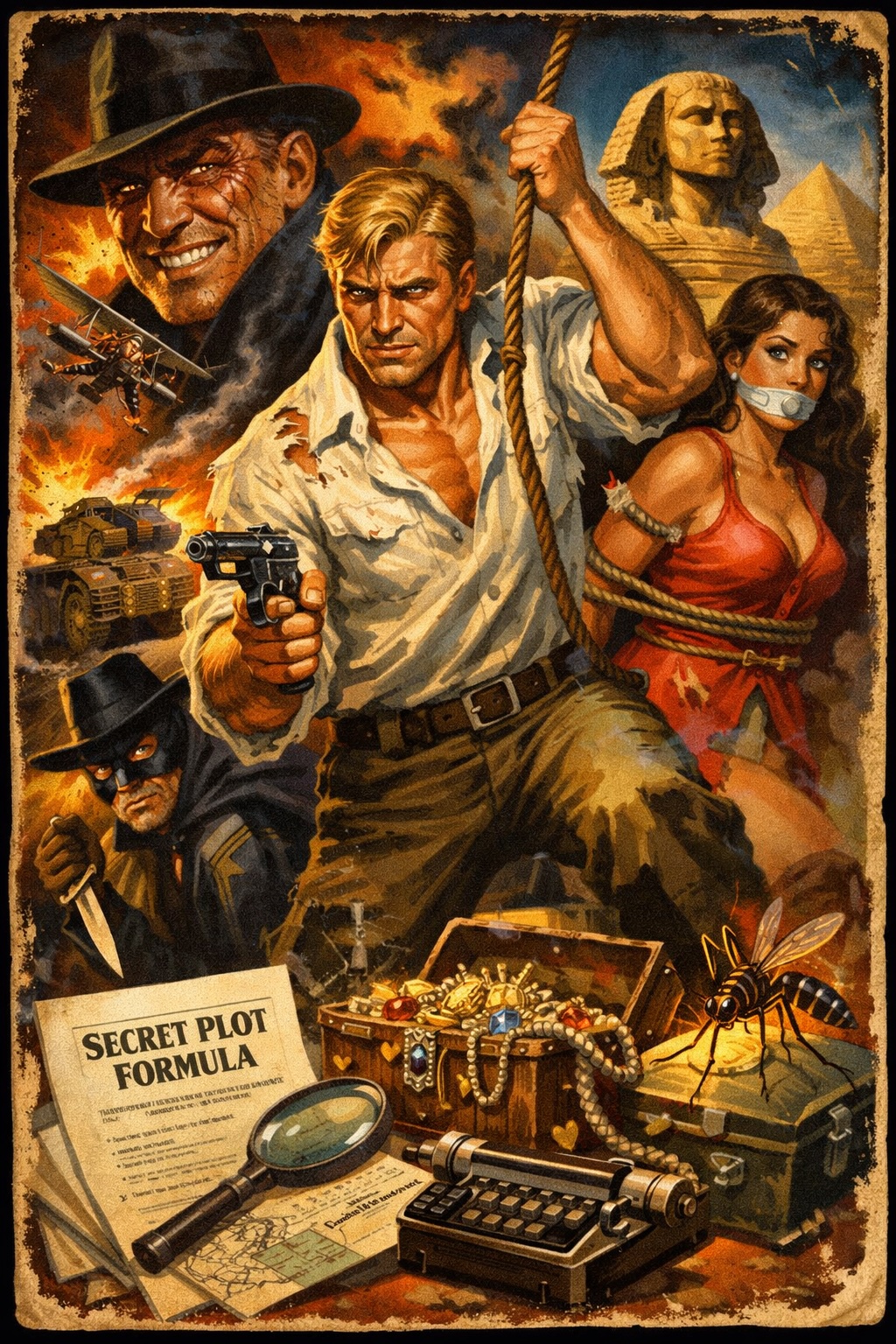

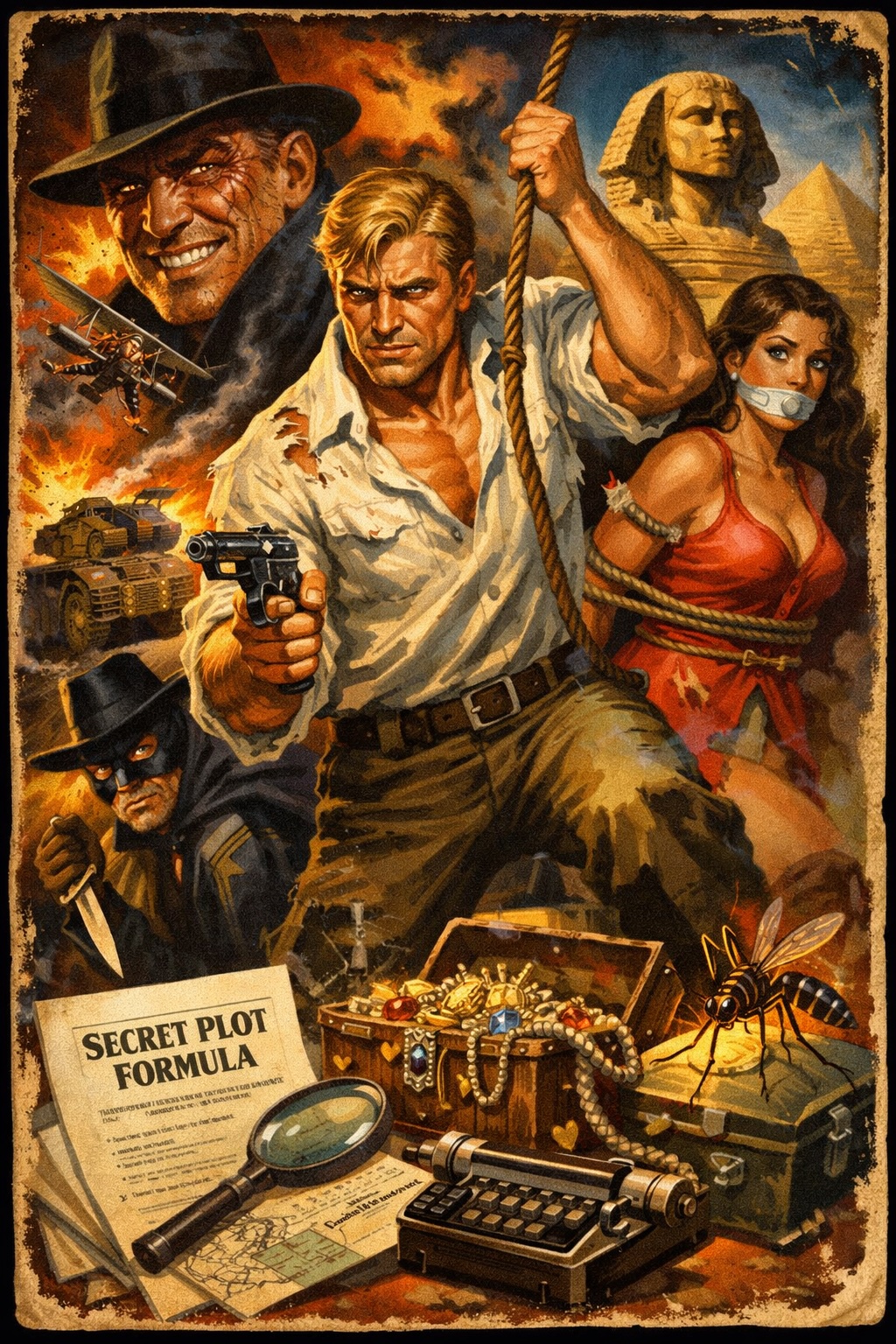

The Lester Dent Pulp Paper Master Fiction Plot

Lester Dent (1904–1959) was a prolific pulp fiction author who wrote hundreds of stories. He is best known as the principal author of the Doc Savage series, featuring a superhuman hero. Dent developed a formula—a master plot—for writing a 6,000-word pulp story. It has proven effective for adventure, detective, western, and war fiction.

Here’s how it starts:

- A DIFFERENT MURDER METHOD FOR THE VILLAIN TO USE

- A DIFFERENT THING FOR THE VILLAIN TO BE SEEKING

- A DIFFERENT LOCALE

- A MENACE THAT HANGS LIKE A CLOUD OVER THE HERO

One of these DIFFERENT elements is good; two are better; three are excellent. It helps to have them firmly in mind before tackling the rest of the story.

A different murder method might include shooting, stabbing, hydrocyanic poisoning, garroting, poison needles, scorpions, or similar means. Writing these down can spark ideas. Scorpions and their venomous bite? Perhaps mosquitoes or flies infected with deadly germs?

If victims are killed by ordinary means but found each time under strange and identical circumstances, that may also work—provided the reader does not learn until the end that the method itself was ordinary.

Writers who leave butterflies, spiders, or bats stamped on victims might conceivably be flirting with this device.

That said, it usually does little good to make murder methods too odd, fanciful, or grotesque.

The different thing the villain seeks should likewise avoid the usual jewels, stolen bank loot, pearls, or other overused prizes. Again, there is a risk of becoming too bizarre.

A unique locale is easy to choose. Selecting one that fits the murder method and the “treasure” the villain wants simplifies matters. It also helps to use a familiar place—somewhere you have lived or worked. Many pulp writers don’t, but it can save embarrassment to know at least as much about the locale as the editor, or enough to fool him.

Here’s a commonly used trick for faking local color. Suppose the story is set in Egypt. The author finds a book titled Conversational Egyptian Easily Learned, or something similar. He wants a character to ask, in Egyptian, “What’s the matter?” He looks it up and finds, “El khabar, eyh?” To keep the reader oriented, it’s wise to make clear—somewhere—what that means. Occasionally the text will explain it, or another character will repeat it in English. What’s risky is stopping cold to translate it outright.

The writer learns that Egypt has palm trees. He looks up the Egyptian word for palms and uses it. This often convinces editors and readers that he knows something about Egypt.

Here’s the second installment of the master plot.

Divide the 6,000-word story into four parts of 1,500 words each. In each part, include the following:

FIRST 1,500 WORDS

- In the first line, or as close to it as possible, introduce the hero and hit him with a fistful of trouble. Hint at a mystery, menace, or problem he must face.

- The hero moves to cope with this trouble—trying to unravel the mystery, defeat the menace, or solve the problem.

- Introduce ALL other characters as soon as possible. Bring them in through action.

- Near the end of the first 1,500 words, the hero’s efforts lead to a physical conflict.

- End the section with a complete surprise twist in plot development.

SO FAR:

Is there suspense?

Is there a menace hanging over the hero?

Does everything happen logically?

Remember that action should do more than move the hero across scenery. Suppose the hero learns that villainous dastards have seized someone named Eloise, who can explain the secret behind the sinister events. The hero corners the villains, they fight, and the villains escape. That’s weak. The hero should accomplish something—perhaps rescuing Eloise—and surprise! Eloise turns out to be a ring-tailed monkey. The hero counts the rings on Eloise’s tail, if nothing better comes to mind.

They’re not real. The rings are painted on. Why?

SECOND 1,500 WORDS

- Heap more trouble onto the hero.

- The hero struggles heroically, leading to—

- Another physical conflict.

- End with a surprising plot twist.

NOW:

Does this part have suspense?

Does the menace grow like a black cloud?

Is the hero really getting it in the neck?

Is everything logical?

DON’T TELL—SHOW. This is one of the secrets of writing. Never tell the reader; show him. (Trembling hands, roving eyes, slackened jaw.) Make the reader see it.

It helps to include at least one minor surprise. These small shocks coax the reader into continuing. They needn’t be profound. One way to achieve this is gentle misdirection. The hero examines the murder room. Behind him, a door begins to open—slowly. He doesn’t notice. The door opens wider and wider until—surprise!—the glass pane falls out of a window across the room. Air flowing in caused the door to open. But what made the pane fall so slowly? More mystery.

Characterization means giving a character memorable traits. TAG HIM.

BUILD YOUR PLOTS SO ACTION CAN BE CONTINUOUS.

THIRD 1,500 WORDS

- Heap still more trouble onto the hero.

- The hero makes some progress and corners the villain—or an associate—in

- A physical conflict.

- End with a surprising twist in which the hero preferably takes a serious beating.

DOES IT STILL HAVE:

Suspense?

A darkening menace?

The hero in a desperate fix?

Logical progression?

These outlines exist to ensure physical conflict, real plot twists, suspense, and menace. Without them, there is no pulp story.

Each physical conflict should preferably be DIFFERENT. If one fight uses fists, that’s enough pugilism for that story. The same goes for poison gas or swords. Naturally, exceptions exist—a hero with a signature move or lightning draw may use it more than once.

The goal is to avoid monotony.

ACTION:

Vivid. Swift. No wasted words. Make the reader see and feel it.

ATMOSPHERE:

Sound, smell, sight, touch, taste.

DESCRIPTION:

Trees, wind, scenery, water.

THE SECRET OF ALL WRITING IS TO MAKE EVERY WORD COUNT.

FOURTH 1,500 WORDS

- Heap difficulties onto the hero even more thickly.

- Bury him in trouble. (The villain has him captive, frames him for murder, the girl seems dead, everything appears lost, and the DIFFERENT murder method is about to finish him.)

- The hero escapes using his own skill, training, or strength.

- Remaining mysteries—ideally one large one held until now—are resolved during the final conflict as the hero takes control.

- Deliver a major final twist. (The villain is someone unexpected; the treasure proves worthless, etc.)

- End with the snapper—the punch line.

HAS:

The suspense lasted to the final line?

The menace held firm?

Everything been explained?

Everything happened logically?

Is the punch line strong enough to leave the reader with that warm feeling?

Did God kill the villain—or did the hero?

Here is a concise summary paragraph added to the end, consistent in tone and purpose with the original material:

In short, Dent’s master plot is a practical blueprint for sustaining momentum, suspense, and reader engagement in a 6,000-word pulp story. By dividing the narrative into four escalating sections, each driven by action, menace, surprise, and physical conflict, the writer avoids sagging middles and anticlimactic endings. Variety in setting, threat, and confrontation keeps the story from growing monotonous, while clear stakes and continuous pressure on the hero ensure forward motion. The formula does not replace imagination; it disciplines it, ensuring that every scene advances the story, sharpens the danger, and earns its place on the page.